Codecraft

software = science + art + people

A better way to put data in code

2014-10-08

I’ve been focusing on esoteric features of language design for a while. I thought it might be nice to take a detour and explore something eminently practical and easy to explain, for a change.

Let’s talk data and tables.

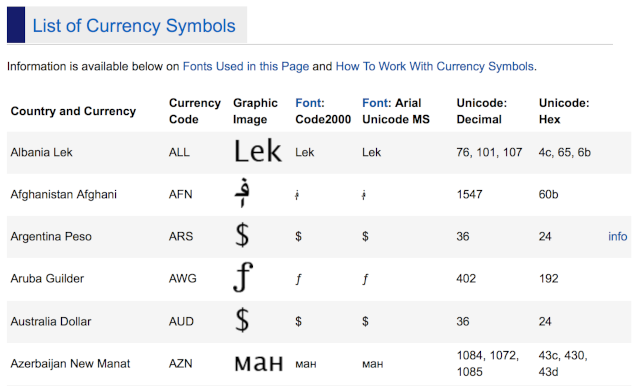

I don’t mean databases — relational or otherwise; I’m talking about tables of data in source code itself. Sooner or later, every coder uses them. We build jump tables, tables of unicode character attributes, tables of time zone properties, tables of html entities, tables of multipliers to use in hash functions, tables that map zip codes to states, tables of dispatch targets, tables that tell us the internet domain-name suffix for a particular country name…

Depending on the language you’re using and the nature of your data, you might code such tables using arrays, structs, enums, dictionaries, hash maps, and so forth.

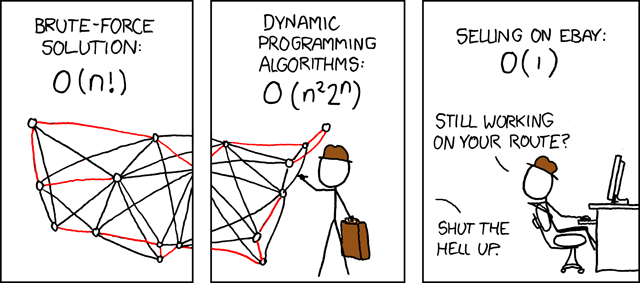

I think this is a mediocre solution, at best. Shouldn’t programmers work on funner stuff, like “traveling salesman” problems? :-)

What's wrong with how we code tables?

What’s wrong? In a word, the fact that we have to code them at all — that’s what.

If all the tables in our code had half a dozen items, the awkwardness of codifying them might not matter so much. But tabular data in code is often large, awkward, and difficult to format correctly. We rarely receive it expressed in a syntax that makes lexers happy.

I recently spent time writing a python script to reformat a 100 KLOC .cpp file that contained generated unicode ngram definitions represented as strings. The strings included bytes > 0x80 and < 0x20, and the compiler was refusing to process the file because it could tell the “source code” wasn’t ASCII.

I’m not sure how many hours I’ve spent doing regex search/replace to put quotes around strings that I copied/pasted from a table on a web page somewhere — but the tally is large. I’ve fiddled with smart quotes, tweaked project defs to declare code pages for my source, line-wrapped by hand across hundreds of lines of data, debugged missing escape sequences due to embedded backslashes, added and subtracted commas and curly braces and line continuations, and all kinds of similar fiddle work.

Coders have better things to do.

Notice that in most cases, data tables like these represent knowledge whose primary home isn’t really code, and whose true owner isn’t an engineer. Coding such data is therefore a setup for communication problems and busy work.

On another recent project, I needed a table to correlate ISO 639 country codes, country names as stored in a whois DB, and telephone dialing prefixes. The providers of whois data helpfully offered a pipe-delimited text file on their web site that showed how their country names mapped to ISO 639, and a little googling gave me an HTML table that mapped those codes to dialing prefixes.

I knitted these two data sources together and build a .h that declared an array of structs to do my mapping. Easy. But I don’t own the data. Because it is “foreign” in the new code home I’ve built for it, I have some lingering problems. For one, what do I do about changes? If Syria fragments or Crimea is no longer a part of Ukraine, I will have bugs in my table, and I will have to hand-edit to fix them once I diagnose the problem. That might never happen, since the owner of the whois data is unlikely to email me about it. Likewise, if phone companies decide that Antigua and Barbuda needs a new dialing prefix, how will I find out? Nobody is guaranteeing that the country-code-to-dialing-prefix table I found on the internet is up-to-date (or complete, or even accurate) — except me.

What would be better?

The world already has very mature ways to deal with tabular data. They’re called spreadsheets and databases. Imagine the master version of some of the types of data I’ve mentioned, and I suspect you’ll be imagining one or the other of these tools as part of the context. Don’t you think the definitive master lists of mappings between cities and postal codes live in postal service databases somewhere? Or that the guaranteed-accurate-and-up-to-date enumeration of stock ticker symbols lives in a spreadsheet at the NYSE or the FTSE?

What programming languages ought to do is allow coders to import data from their definitive sources — or at least from a small handful of exchange formats like CSV and XML — with no intermediate hand coding. In other words, I want what I’ll call direct compilation of data from native formats. If I create a currency-exchange app that needs a currency conversion table, what I want is to write code like this:

table currency_info:

columns: id(enum), symbol(str), name(str), exchange_rate(float)

rows: Attach("latest_currency_info.csv")

If a compiler supported such code, it might read the attached .csv file, parse it using CSV rules, and create an array of structs where each struct instance is a tuple or row of data. The array would be indexed by ID, a value that the compiler would generate in the same way enum values are assigned. The end result would be an a static constant array, exactly as if I had hand-coded a manual translation of the data. Essentially, this is the technique I recommended when I wrote about how to avoid breaking encapsulation with enums.

Think about the advantages for a minute. Christine Lagarde isn’t going to call me up or help me write code if the IMF decides to make loans in Bitcoin (to pick a ridiculous example) — but I can write a cron job that downloads data about accepted currencies worldwide, as published on xe.com. Suddenly my code is up-to-date. I never have to do reformatting work, and I don’t have to worry about code getting out-of-sync with reality.

This isn’t rocket science, but it’s remarkably powerful. You no longer need to use programming language syntax to describe data — you can use a familiar, standard data representation language. That means non-coders can give it to you directly. Data sources turn into code with minimal effort.

At work, I maintain code that helps categorize content on the web. The set of possible categories is in a coded table in both C++ and java, but it is not chosen by engineers — product managers and executives debate about what’s most useful to customers, and they periodically change their minds. If I had compilers that supported the behavior I’m advocating, I could tell my product management to email me a .xlsx whenever they make a change, and my reaction time would be minutes. And I could be certain that the C++ and java versions of the table were identical, since they used the same input data.

Getting fancy

I can think of enhancements that would make such a mechanism even more powerful:

- Let tables be re-sorted during import.

- Let tables be indexed by multiple fields.

- Support joins, either during import or by making tables connectable at run-time. (Remember my problem where I had to connect whois country names and telephone dialing prefixes, with an ISO 639 country code as a common column?)

- Allow columns that are populated by formula (evaluated at compile-time) instead of by an actual data value. Besides generating new or composite data, this would give us a way to normalize reliably.

- Support assertions about imported data, to guarantee integrity.

- In addition to supporting a rich set of input formats, allow a coder to write custom importers.

- Let coders reorder or suppress columns during import.

Making it real

As you might have guessed, direct compilation of data from native formats is a feature of the intent programming language I’m working on. But I think this technique might be implementable in some other programming languages, even without changes to a spec.

In java, you might be able to implement a custom class loader that generates bytecode for a table when given a .csv as the URL it should load from.

In python and perl, you could probably implement a class that generates dictionaries from a statement that looks quite similar to an import.

In C++, you could use a custom build step and an external app to generate a table from a csv. A bit klunky, but usable.

You might even be able to write a SWIG module that would do this in a whole bunch of different languages, all in one go.

If any of you have great ideas (or implementations), please share them.

Comments-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Laurent Caillette, 2014-10-08:

Hi Daniel, I think I understand what you mean. I wrote something to read an indexed table of Unicode characters: https://github.com/caillette/novelang/tree/master/modules/unicode-generator-plugin/src/main/java/org/novelang/build/unicode https://github.com/caillette/novelang/tree/master/modules/unicode-reader/src/main/java/org/novelang/parser/unicode Reading tables makes the world feel more annoying than it should be. In the example above, first I scanned the bundled 1.2-MB file the first time I was looking for the official name of an Unicode character. But there was such a slowdown when using the debugger that it drove me crazy and I decided generate an indexed file. This was boring, but not so hard. I should consider myself happy because the Unicode standard doesn't evolve a lot. "Evolution" is the keyword. We already have all kind of useful parsers, CSV importers, XLS readers to do the job. The real problem is, what happens when the data we are generating code from does evolve? Compiler might tell us. We could have tests doing clever checks. But the underlying looks like a versioning problem. Or, more broadly, a continuous delivery problem. You probably met those big projects with some business analyst carefully spoonfeeding databases with reference data, that we ship later as database dumps. Should they switch to git and Maven? I think so.

Daniel Hardman, 2014-10-08:

Laurent: Thanks for the insightful comment. I agree that versioning is a tricky question. Data does evolve. On another project that I recently did, I had to ingest large numbers of records. I barely finished the ingesting code when the data provider decided to add new columns to the data. It was frustrating. I don't know of any silver bullet that makes the continuous delivery challenge go away, but I'm interested in learning about things that my smart friends have done. I guess with unicode, change happens seldom enough that it's not a problem — but how have you solved that issue in other scenarios?

laurentcaillette, 2014-10-08:

I'm currently working on a financial application, which describes a few hundreds of built-in financial products. The buisness analyst is truly editing Java code to create new products. I can ship a fresh version in less than 15 minutes, and restarting the server at the end of the day causes the new products to go live. Of coures some buisness contexts don't allow that. But this shows that the line between code, data, and configuration is somewhat blurry. There are so many applications with complex scripts that live outside a version control system. Users love configuration over standard programming, because the delivery system takes too much time for them. But configuration bugs are as nasty as others. (In fact they are worse because there are no real tools to track them.) I've some ideas about an event-sourcing application that makes code, configuration and data flow through the same pipeline, with ability to backtest code and configuration changes. I described it here (Google translate is your friend. Among various horrors, it says "application heart" where I would write "application core", but it looks readable otherwise.) https://groups.google.com/forum/#!msg/techos/h74Se445O3g/0z7bqNfVX5IJ https://groups.google.com/forum/#!msg/techos/ZR40eFy0xaA/uFLX9YVuySAJ https://groups.google.com/forum/#!msg/techos/4wjoo2a_0K0/VfNs1Fm4eAwJ

Daniel Hardman, 2014-10-08:

I went and read your posts on the techos forum. Very interesting. LMAX sounds like a fabulous design. I recently built a system that has a lot of conceptual overlap; it uses the Event Sourcing pattern that Martin Fowler described (and that you referenced) to capture the evolving state of a supercomputer cluster over time. See http://j.mp/1ndmah4. But I don't think I did it quite as well as the LMAX system does. Your insight that configuration changes can be represented by messages, the same as any other event, is awesome.

laurentcaillette, 2014-10-08:

Thank you!

davidrea, 2014-10-09:

This is a particularly-tricky problem in embedded systems, where there can often be multiple processors that must "agree" on the meaning and significance of keyed data. Enums are a favorite mechanism, but give rise to synchronization issues when processor firmware versions evolve asynchronously (or when embedded systems must interact with the outside world; i.e. through PCs, mobile devices, IoT interfaces, etc.) - still working on a solution here!

Daniel Hardman, 2014-10-09:

Embedded systems isn't an area where I have deep expertise; thanks for adding that dimension to the discussion. I think the Internet of Things is going to make this sort of environment more and more a part of the experience of the average developer — and it's going to make this versioning/evolution problem even more pressing.

trevharmon, 2014-10-11:

The only example of this type of thing working really well that comes immediately to mind is tzdata, However, take a look at the Wikipedia article (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tz_database) to see what's taken to put that in place. And, this case, we don't interact with the data directly, but instead use the APIs. Building that type of structure does let us swap out data as necessary, but is overkill in many, many situations.

Daniel Hardman, 2014-10-11:

Trev: I first gained an appreciation for the complexity behind tzdata when I had to implement timezone-aware date/time conversion for filesystems *without* any OS services or API at all (I was doing filesystem surgery in a rescue environment that barely had a kernel, let alone a "real" OS). So the example you cite is an interesting one to me. What conclusion do you draw from the observation that a complex ecosystem to support data-sensitive code is often overkill? Should we live with flaky/incomplete/sometimes wrong captures of the data? Do you think being able to consume data in the simple way I describe will make things better, or will just encourage sloppiness?

Andy Lawrence, 2014-10-12:

Daniel, The problem you outlined is one of the main features I have been trying to solve with my Didget Management System. The "Database Table" Didgets and "Tag" Didgets do a lot of what you describe. Files have traditionally been a great way to share unstructured data between programs. One program creates a file (.jpg, .xls, .csv, .doc, etc.) and another program can search for it within the directory hierarchy, read it in, and use it (or even add value to it if it has write permissions). The downside is that there are often multiple formats in which unstructured data can be stored, so all the programs sharing the data have to be on the same page with regard to data formats. Structured data, on the other hand, has not been so easy to create and share. Ideally, you want to be able to download tables, columns, or entire databases from the internet and have a dozen or more programs access one or more elements without needing to: 1) Install and run a RDBMS. 2) Set it up with the proper schema. 3) Import all the data. and 4) require the programs to figure out how to access the database. Stuff like ODBC drivers can help, but it still takes a lot of work just to create and share a simple key/value store of things like the country codes and dialing prefixes you described. Tag Didgets were designed to make this super easy. Using them, you can create or download a table with 3 or 4 (or 100) columns defined. The table is a just list of all the columns it contains. Each column is a separate key/value store pre-populated with values. Any program can read values from one or more columns as easy as it can open a file and read in the data. A program can discover Tags in the system as easy as it is to find all the photos. Versioning will make it so you can quickly check for updates from a server. If your local table is 2 versions behind the current one at an update URL then simply download the new version and start using it. (Kind of like doing a "git pull" from a code repository). If the new version has added, changed, or deleted columns then you don't have to redo your schema or fix up a database. Your program can still interact with it. The beauty is that the structured data is already in a usable format that multiple programs can use without "importing" it into some custom table. The program doesn't have to figure out how to parse some CSV, XML, or Json file or perform all kinds of integrity checks on the data to validate it.

Daniel Hardman, 2014-10-12:

Andy: I think didgets shows a lot of promise. However, when you say in your final paragraph that didgets data would be in a usable format without importing it into some custom table, aren't you glossing over the effort that would be required to import it into didgets, and the code that would be required to call a didgets API? Or are you assuming a world where didgets has become pervasive and therefore transparent? If I make any headway on the intent programming language, perhaps I could figure out a way to license didgets to ship with it... I am also interested in seeing if I can license some of your bitmap code (that's an area where few if any programming languages provide something out-of-the-box [vector is pretty weak], and it would be nice to ship a standard library that addressed such a need).

Andy Lawrence, 2014-10-13:

Obviously things would be much simpler if Didgets were ubiquitous like file systems and just about every program was written to use the Didget API for all persistent storage functions. (I can dream can't I?) But it really isn't that hard to import data into Didgets. Using our browser application, one can drop a simple CSV file on a definition and it will automatically generate a table and each column and import all the data. Using our API, a program can then interact with that table or with individual columns to extract out values according to search criteria (e.g. Fetch all country values that start with the letter 'Z' or Fetch all zipcodes between the numbers 85000 and 87500). All the code to handle the values is embedded in the library. A program could access lots of different kinds of Didgets with just a few lines of code. It wouldn't need to import the data into its own memory table and implement its own search functions in order to find a value or a set of values. I think the code in the browser which processes queries and displays all the results in a table format is only a couple hundred lines of code. I am open to working with anyone who is interested in using the Didget technology. I have also thought about promoting my bitmap class used by the Didget Manager into its own Didget type. Bitmaps would thus become first class objects where any program can create and use its own set of bitmaps. Bitmaps could then be shared, protected, replicated, and synchronized across containers just like every other Didget.