Codecraft

software = science + art + people

Baby Steps

2012-10-24

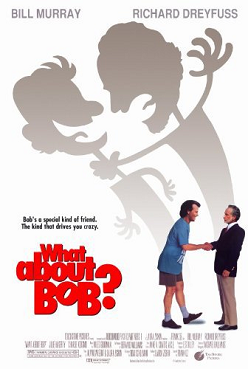

If you’ve seen the delightful comedy movie, What About Bob?, you are no doubt smiling at my title.

Bob is a neurotic and thoroughly irritating patient who depends on his psychotherapist for lots of emotional strokes and life coaching. He ingratiates himself with the therapist’s family and gets himself invited to be their guest on a weekend getaway, against the protests of the therapist. He then proceeds to drive the therapist crazy.

One of Bob’s favorite phrases is “baby steps,” which captures the therapist’s advice to solve problems a little bit at a time, rather than in overwhelming chunks.

“Baby steps” is surprisingly good advice for many questions in software design. It doesn’t apply in all cases, but it applies far more often than it ends up being used.

The Purpose of Design

We create UML diagrams, personas, design docs, lo-fi mockups, and other artifacts to capture our architectural thinking because they provide us with a roadmap of sorts. We need to identify and steer to a consistent point of the compass if we want to produce complex artifacts that meet customer needs. The bigger and more diversified our teams get, and the more moving parts we’re orchestrating into our software, the more important this is.

However, all of these artifacts are means to an end. To whit: coordinate the collective brain power of the team toward a clear goal, such that the final product exemplifies prioritized and rationally chosen requirements.

If you buy this assertion, then you should also see that in some circumstances, lots of up-front design work is not a good investment. What if:

- You're not confident that you're choosing the right set of requirements?

- You're not confident that a particular design will be appropriate?

- The entire team already understands the general direction?

In each of these cases, it may be smarter to start taking baby steps now, rather than planning giant steps to the Nth degree.

If you want to vett your requirements, and you don’t have a pool of customers to survey, then perhaps it would be smarter to do something quick and dirty and use it to test the waters, rather than designing an elegant and comprehensive solution. I have seen companies fail to take baby steps in this scenario on many occasions, and the usual result is a huge waste of time and energy. We simply guess wrong too often, when the scope ornge of our guess is overly ambitious.

If you wonder whether design A or design B will be appropriate, then again, perhaps you should start implementing as an experiment. I never cease to be amazed at how quickly designs develop a smell (if they’re bad) or a luster (if they’re good) once you start using them. If you worry that it would be too expensive to code up two alternate solutions, consider using role-play centered design to let humans substitute for key modules with almost zero overhead.

If the entire team is already headed north, and your design just draws a northerly vector on a map, then maybe a careful, formal design isn’t worth the effort. Teams that push for more thoughtful up-front planning often make the mistake of requiring the same design artifacts for all plan inputs. This generates useless busy work for a portion of the features on the docket.

When baby steps are a bad idea

Big steps are a better choice when all of the following are generally true:

- You are confident that you understand the scope of the problem, because you've done detailed market research and competitive analysis. You can point to an existing system and say, "It must do this."

- Anything less than a full solution will be a market disaster. (This happens, but not nearly as often as we think.)

- The chances of making a wrong choice are high.

- Forgiveness for making a wrong choice is low or non-existent.

Splitting hairs

What I’m advocating here might sound a lot like a caution against analysis paralysis, but the two ideas are distinct.

Sometimes, your design might not be paralyzed at all — sometimes you’re coming up with all kinds of great ideas, and you sense a grandiose vision unfolding. Maybe you’re loving the design phase.

I’m claiming that if your design takes you too far into the future, no matter how good it is and how much momentum you feel, you might be better off tng baby steps on your implementation instead. I’m making this claim based on the observation that it’s easy to overbuild, and it’s easy to make mistakes by extrapolating too far into the future.

You might also think that baby steps are a repeat of my advice to put a stake in the ground.

Again, there’s overlap, but the ideas aren’t quite the same. Putting a stake in the ground is a way to get off the dime when consensus is lacking, or when analysis is impossible. Baby steps advice applies even if you don’t need a stake.

Why baby steps

Here is a fundamental truth that many organizations don’t understand: building a new product or feature is as much a learning activity as it is a coding and testing activity. The output at release time is NOT just some binaries and documentation — it is a new mental model in the minds of the entire dev, support, sales, and services teams. Always, learning takes time — and often, you have to learn by doing. You cannot front-load it all into a compressed “design phase” or “sprint 0” and expect that as you exit that time, all your learning will be over.

Which is why baby steps make sense.

Do as much preliminary design work as you truly need. Make the best decisions you can. But then, as quickly as you can manage, you need to get in the mode of putting one foot in front of the other, and learning how to walk.

You already know this works; you used this strategy as a baby.

Action Item

Next time you're given a design assignment, use role-play centered design or other techniques to start experimenting as quickly as possible.