Codecraft

software = science + art + people

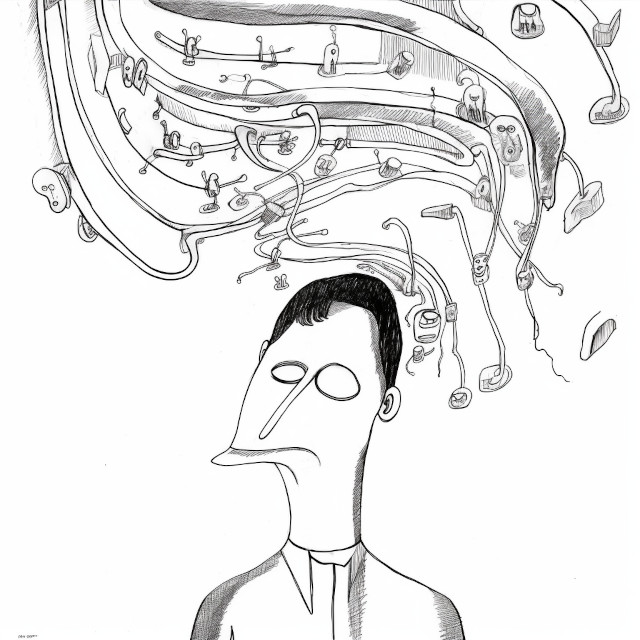

Coping With Organizational Alzheimers

2012-10-12

Years ago, an astute manager summed up a problem that I had only vaguely intuited up to that point in my career.

“A big problem with most companies,” said Roland, “is that they have no institutional memory.”

As I recall, Roland was describing capricious political winds, and lamenting that the only form of loyalty a company has to employees is the kind they put in writing. As soon as there’s major M&A activity, or HR decides to rebalance salary allocations, or an incentive program gets adjusted to the latest management fad, all recollection of old priorities and soft obligations vanishes in a puff of smoke.

If anything, Roland was understating the problem. Companies routinely panic and change strategy half-way through an investment cycle, because they can no longer articulate the rational analysis that led them to take a plunge. Buzz floods the internet about some innovation that makes everybody excited, but we forget that we’ve heard the idea before, behind some different terminology. (Are you nodding your head because “cloud” in the last few years is just a recycling of “utility computing”from circa 2000? Trev, a colleague of mine at Adaptive Computing, showed me a dog-eared copy of The Challenge of the Computer Utility, by Douglas Parkhill. It’s all there — XaaS, elastic and on-demand, in 1966. And who knows — maybe sci-fi writers or the designers of Eniac had thought of it even before Parkhill…)

But I digress.

One particularly insidious form of forgetfulness in software relates to technical debt. Another colleague, Doug, reacted to an expedient workaround this way:

My one regret with this is that by doing something that is good enough it will never get the attention it might deserve to be made better. This happens each release: we make compromises at the very end to get it out the door, promising ourselves that we'll revisit it later.

Folks, we don’t keep these promises to ourselves very well; Alzheimers is endemic with regards to technical debt. The only thing that saves us is that engineers or product managers stumble upon the consequences of earlier kludges, which reminds us of the awkwardness from time to time. And there are enough passionate people in our industry that sometimes when an issue like this pops, we find a way to do it right. Sometimes.

I have two suggestions about how we can cope.

Suggestion 1. Log a new kind of ticket.

In most disciplined software companies, product planning captures what needs to happen in the next release. If you’re doing waterfall, you write specs; if you’re doing agile, you write stories. Either way, these artifacts commonly result in granular tickets that get assigned to implementers and testers. The tickets are then managed carefully until everything’s been either closed or deferred, and a release comes to pass.

That’s all well and good. But kludges aren’t visible if the only thing you ever manage is what. Kludges satisfy what; they’re yucky because of how.

What we need is a disciplined tracking of how.

“We already do that!” I hear you say. “We have design docs, UML diagrams, photos of whiteboard discussions, architectural reviews…”

Yes. That’s all well and good, too.

But those mechanisms create alignment in the brains of people, and in their short-term behavior. Those people are part of an organization that has Alzheimers.

They need a memory aid.

Architects, log a ticket about how something must be done. If it gets deferred due to short-term expedience, you have tangible evidence of the debt that’s been incurred, and in the next release cycle, management will be forced to reckon with it. If the ticket gets ignored, give the”blocker” priority a whirl… :-)

Suggestion 2: Be the change you want to see in the world.

If you’re a manager: Orgs that believe in kaizen are great. But if you always drive kaizen from the top down, you’re missing the boat. What you need to do is let trusted engineers do kaizen from the bottom up. Every good engineer that I know has a few items they’re itching to improve. Let slip the dogs of war and see what happens.

If you’re an individual contributor: find a way. Don’t sit around and wait for your manager to tell you you’ve been assigned to refactor. Just do it. Advocate. Read Seth Godin’s book, Poke the Box. Then go poke.

A note of caution

Not every itch justifies a scratch. Engineers have a tendency to envision the ideal, and to love the freedom to go create it without mapping that activity back to hard business constraints. I know I do! :-)

If you’re a manager, notice that I said you should give this freedom to trusted engineers — not just anybody. Trust folks that can tell you how 2 days of effort will delight customers and save the company thousands of dollars. They’ll probably take 4 days (or 6, if they’re as bad at estimating as I am) to get the job done, but at least they have a tightly defined task with a specific payoff. Don’t trust “teenage” engineers who try to sell you on total rewrites.

If you’re an engineer, earn the trust I’m talking about.

Action Item

Find three examples where technical debt has been conveniently forgotten, and do something to keep the memory loss from becoming permanent.

Comments-

-

-

-

SutoCom, 2012-10-12:

Reblogged this on Sutoprise Avenue, A SutoCom Source.

ryancorradini, 2012-10-16:

The “how” tickets are a great idea, but in my experience, they frequently tend to end up in the forever-in-the-future “unobtainium” release, because there are *always* going to be new feature requests / legitimate bugfixes / etc, and those will always take priority over refactoring tasks. That said, sometimes when I have a new task that touches on one of these needs-to-be-rewritten code blocks, if I can justify it, I do the refactoring anyway, guerilla-style, as part of the new feature. The challenge is knowing when it’s worth doing so.

Daniel, 2012-10-16:

Ryan: You've got a nice way with words. The "unobtanium release" made me laugh. So true. Sigh... Martin Fowler dedicated an entire book, Refactoring, to the question of how to make sure needed changes don't languish. It probably isn't fair to try to boil him down to a single pithy piece of advice, but I'll try anyway. He advocates changing our perspective on refactoring so that it's no longer a behavior separable from maintenance/improvement/extension. Instead, refactoring becomes a sort of dialog that you always have with the code as you evolve it into its next form. If you do refactoring that way, it just happens naturally, and code remains very healthy. This is a radical change of mindset, but it seems to me that it would help us in many ways.

ryancorradini, 2012-10-16:

I like the concept of a constantly-evolving codebase. That kind of approach would also enable some potentially interesting "code health" metrics derivable from your source control system. (e.g. percentage of code change between releases/milestones, etc). I'll have to look up that book, thanks for the recommendation. As an aside, your link to Steve Yegge's post spurred some productive conversation at work. Always nice when that happens.