Codecraft

software = science + art + people

Mountains, Molehills, and Markedness

2014-07-28

In my previous three posts, I explained why the semantics of programming languages are introduced “marks” — a feature of the intent programming language I’m creating — and gave you a taste for how they work.

In this post, I’m going to offer more examples, so you see the breadth of their application.

Aside

Before I do, however, I can’t resist commenting a bit on the rationale for the name “marks”.

In linguistics, markedness is the idea that some values in a language’s conceptual or structural systems should be assumed, while others must be denoted explicitly through morphology, prosodics, structural adjustments, and so forth. Choices about markedness are inseparable from worldview and from imputed meaning. Two quick examples:

- Chinese generally doesn't inflect tense/aspect, but when necessary, it marks utterances in the past or future using extra particles. Contrast "我吃" ("I eat" or "I am eating" or "I habitually eat" — or even "I will eat" or "I ate", if the speaker considers tense/aspect irrelevant or knowable from context)

::"我吃了" ("I ate" [explicitly in the past]). - In languages that have a grammatical gender, nouns are often marked to indicate a category that the linguistic community deems more semantically rich/interesting than unknown/neuter. Contrast English "I saw some lions"

::"I saw some lionesses"; Spanish "Vi algunos leones"::"Vi algunas leonas"; and German "Ich sah einige Löwen"::"Ich sah einige Löwinnen". In each case, the first form doesn't make any particular claim about gender, whereas the marked form does.

In all human language, meaning is powerfully influenced by patterns of markedness. We pay attention to marks. Whether we’re raising our eyebrows, selecting words with care during an debate, or straining to understand a friend on an iffy cell phone connection, we key off of their presence or absence. We do it intuitively and constantly.

Yet for all their power, marks are unobtrusive and cheap to use.

That’s a happy combination.

Markedness in programming languages

Of course, markedness already manifests in programming languages, even if you’re not using my “marks”. Depending on whether you’re in java, C++, or python, the default visibility of class members is package, private, or public — all other visibilities must be marked. Constness is marked in C++. Alignment of data structures, casting, partial template specialization, scope of closure variables, and many other features all embody markedness rules in one way or another.

Unfortunately, the literalness of programming languages, and the fundamental assumption that the purpose of a language is exactly and only to embody instructions that get translated to machine code, has caused markedness to be mismanaged. I’ve already written at length about the semantic gap between code and human software development activities — the lacuna humana. That arises partly because of markedness problems; go back and read my blueprint for marks and see how markedness can’t propagate or evaluate without the infrastructure I describe.

Another consequence of markedness mismanagement is clumsiness and verbosity. Human languages are parsimonious; default cases tend not to be the marked ones. Even when marks do appear, they propagate meaning without ad nauseum repetition. But programming languages have historical baggage that flips markedness on its head — the threadsafe, bounds-checking, non-blocking, const-correct versions of features that we should use by default all require extra marks. Think sprintf_s, rand_r, the std:: namespace… Think smart pointers versus raw pointers. Think Hoare’s billion-dollar mistake. How many explicit assertions and preconditions have you written over the years, to sanity-check stuff that should always be true (if (myArg == null) throw Exception("Can't be null.")…), instead of writing code to allow a few corner cases?

More Examples

Hopefully I’ve convinced you that markedness matters. I think it’s a mountain, rather than a molehill.

But just in case I haven’t, here are more scenarios to think about. As you read these, keep in mind what you already know about marks: they have full access to the code DOM at compile time; they propagate in sophisticated ways; they can generate code; and they can attach to constructs that traditional code ignores, such as requirements, human teams, and so forth.

- Release readiness and dev milestones can be codified with marks.

Imagine that your team has a policy that once you hit the "UI freeze" milestone, .properties files can't change, because strings have been sent out for translation. You place a single mark on a codebase, saying that you're now at the "UI freeze" milestone. You write logic for your mark that says it can't attach if any .properties files are checked out from git. When you compile, the compiler throws a semantic error if the mark is present but .properties files are checked out.Or imagine that you have a "release gauntlet" checklist. Before you release, you must certify dozens of items (gold master binaries have been scanned for viruses, release notes are finished, branching operations in Perforce are done, "beta" has been removed from the product's version stamp...). You create a "ready to release" mark that tests completion of each item in the gauntlet, place it on the product, check in files that record your progress, and let your compiler tell you when you've achieved your intentions.On a less grandiose scope, I've often wanted a way to advertise that code is "API complete" even though some parts of it are only backed by stubs — or I've wanted to tell a tester when I'm ready to hand something off. Marks are perfect for this.

- Stubs, experiments, and incomplete implementations are best marked, instead of using the familiar

// TODOcomment convention.If you have a queryable DOM and TODO marks that can propagate powerfully, you can quickly get a picture about how much unimplemented functionality lurks in a codebase. (Notice how the presence of a "not finished" mark could interact with the "ready to release" mark I mentioned above...) - Marks can provide intuitive shortcuts for semantic bundles.

How many functions in your codebase take a filesystem path as a parameter? How many of these parameters must identify a file that exists with appropriate permissions — or a folder that will be created? Using a mark to generate all these preconditions is a lot cheaper than expressing all of them yourself, over and over again. In

intent, marks are exposed as parts of interfaces, which means you don't even have to document these preconditions once you add the mark; it all just flows.The familiar pattern of passing args to constructors, and using those args to initialize member variables, can also be short-circuited with a "copy args" mark. The method of this mark that generates code can inspect parameter names and the names of member variables, and generate assignment statements for any that don't already have overriding assignment logic in the body of the constructor. And because marks propagate, you can attach a "copy args" mark to a whole class and get this behavior on all of its constructors — or even on a whole package or codebase, if you like. Since you can attach marks with implicitly affirmed semantics rather than just binary on/off, you can use a broad scope but safely override (explicitly deny the "copy args" mark) where you need to.A mark could assert that a class is threadsafe. The compile-time code for this mark that tests bind-ability could inspect the class to see if it has any mutable state, or if it calls any functions marked "non-pure". - Marks can make unit conversion seamless.

One of my pet peeves is parameters named

timeoutorbandwidthinstead oftimeout_millisecsorbandwidth_mbps. How many times do we have to accidentally hang a program by passing "10000" as thedelayarg (discovering to our chagrin that we provided seconds instead of milliseconds) before we get religion about making units explicit?Well, marks can easily make units explicit, painting whole codebases as millisecond-oriented or UTC-oriented at a single stroke. And inintent, these marks show up in generated docs, without the programmer writing redundant javadoc-style comments. But they can do better than that — their code can provide compatibility checks (weight can't be converted to kilograms without a key assumption) and even conversions at compile time. Thinkstd::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::millseconds(25));on major steroids. - Marks can identify aspects and inject AOP-style behaviors.

Imagine that instead of writing thousands of

Log(severity, func, lineNum, msg, ...)statements, you simply painted your code with a smart mark that knew to generate logging. Imagine that the logging strategy used at runtime could be plugged into that mark using IoC techniques. Imagine that the mark could look for functions that you mark as "untrusted" or "error prone" (another use for marks — arbitrary tagging) and dial up logging on those. Imagine that it could interact with another mark, "performance-sensitive", and dial back its aggressiveness.What if, instead of choosing between specialized builds and manually instrumented code to study performance, you could mark codepaths that are interesting to profile — and then inject profiling to those marks, IoC-style? Better yet, imagine you could derive the set of interesting codepaths by examining the propagation and intersection of other marks. Imagine you marked quantities at key places in your code ("I expect this container to hold hundreds of items, and that one to hold tens of millions"). Combine this with the idea that all functions in a standard library could be marked for whether they used the file system, the network, the heap, mutexes, and other key resources — and you could probably predict many bottlenecks at compile time. (Of course, there are limits to what you can predict. :-)

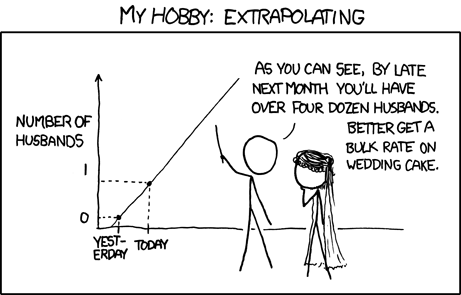

image credit: xkcd - Marks can generate, describe, and enforce error handling.

Want to make sure your callers check the error you might return? There's a mark for that. :-) (Actually, there are compi extensions for that today, in some situations. But you can nuance the behavior, and propagate their semantics, so much better with marks.)Want to give callers the option of short-circuiting expensive checks in a function that will be called billions of times in certain codepaths — but preserve those checks for casual callers? Instead of writing two versions of the function, you could mark conditionals in your code as applying to untrusted callers, and let the compiler figure out who's trusted based on propagation of other marks in the codebase.Marks might be used to generate code for pain detecting algorithms.Imagine you could declare remediation strategies for common problems (Internet down? Retry in 5 seconds. Out of disk space? Flush temp folder.), and simply mark functions as using these strategies across all code you write. Imagine if you could formally describe/recommend remediation strategies to your callers, for errors you returned.

- Marks can delimit temporal boundaries.

After you've finished reading your config file, perhaps your app is now fully initialized, and should never need to read from disk again. You could place a mark at that point in the code, using temporal propagation to say that all codepaths beyond it should be file I/O free. This could be enforced at compile time. It could also generate useful security information at run-time.The problem I brought up in a previous post, about certain methods only being callable at certain points in the lifecycle of an object, can also be solved with temporal marks. State machines become self-documenting.

- Marks can make coupling and cohesion obvious.

I already gave the example of GPL/copyleft effects in a codebase, and how they could be detected with marks. Other types of coupling are manageable with marks as well. Writing a mark that says, "Don't allow any code in Component A to depend on Component B at compile-time" is trivial.The complement is also possible. Suppose Component A, function

aaa()eventually calls Component B functionbbb(), and one ofaaa()'s parameters is a direct pass-through tobbb(). You could document this interaction — or you could create a "passthrough" mark that hyperlinks the two and copies across all relevant semantics. This makes the dependency obvious and saves you the effort of writing and maintaining redundant code and docs.

Final Thoughts

This post would be incomplete if I didn’t acknowledge the limitations of marks. My friend Trev Harmon (@trev_harmon) was asking me the other day how much I thought my ideas overlapped with the goals of the semantic web. Marks are not nearly that ambitious. Although they expand the scope of semantics in programming languages in important ways, they can’t turn code into a fitting conveyance for all human communication. They work well within the domain-specific language of software development.

Another of my friends, David Handy, pointed out that propagation of marks through a call graph gets problematic across closure boundaries and function pointers. That’s quite true, and I’m not sure how surmountable it is.

So marks can’t butter your toast, or write poetry. :-)

Still, I think they’re a useful innovation. I’m hoping that smarter minds than mine can pick up on the kernel of the idea and take it to cool new places I haven’t yet imagined. My friend David also pointed out some cool ways that marks could be used to gather statistics, which I had not considered. What else will you dream up? If you’re interested in collaborating, let me know. Also, I would appreciate you sharing this series of posts with people who don’t read my blog; I’m interested in broadening the conversation as much as possible.

Comments-

-

-

-

Dennis, 2014-07-30:

Just one little correction to the German example in section "Aside". You use the word "Löwin" as genderless expression, but this is the female lion. Whereas "Löwinnen" is the plural of "Löwin". If you wan't to correct it, it would be "Ich sah einige Löwen" :: "Ich sag einige Löwinnen". But nevertheless thank you for sharing your insights!

Daniel Hardman, 2014-07-30:

Thank you so much for the catch, Dennis! I've updated the post.

David H, 2014-08-07:

The additional use cases for marks that you have described here look much more challenging to implement than the ones you gave previously. The earlier use cases could have been implemented by examining a call graph and a DOM of the compiled code. But the use cases involving temporal boundaries, wouldn't those require more sophisticated flow analysis? So, if difficulty of implementation is not to be considered at all, then I can add some more use cases to your list. :) How about marking variables that contain direct user input? Or that contain data POSTed from the internet, etc? And then have the compiler make sure that you never use untrusted input e.g. to form SQL expressions, nor pass it to an exec() function call, etc. How about marking functions that should only be performed by users with admin privileges? How about marking functions that should only execute within a security sandbox? Or, conversely, marking those functions trusted to make changes outside of the sandbox, making everything else restricted? There are probably a lot more security-related rules that, if your marks system was fully functional as you described, could finally be enforced.

Daniel Hardman, 2014-08-07:

Excellent notes, David. The one about direct user input is a great use case, and a piece of cake to implement — and I think it would even be possible to take most of the burden off of the coder, because functions that receive direct user input can be painted with a mark that propagates to anything that calls them in an assignment. This makes it so the very act of calling something like sscanf() can automatically cause the variables that get set to acquire the "direct user input" mark, without the coder lifting a finger. You are right that temporal propagation is harder to implement than some of the other ones. Maybe I'll have to defer that one if it proves too challenging — although I have some ideas about how it would work, and they seem feasible in my mind. I guess we'll see when I get there. At the moment I'm still in the early stages of lexing/parsing... The whole security angle is huge, and I'm hoping someone who's got a deep background in vulnerability analysis can chime in with wisdom.