Codecraft

software = science + art + people

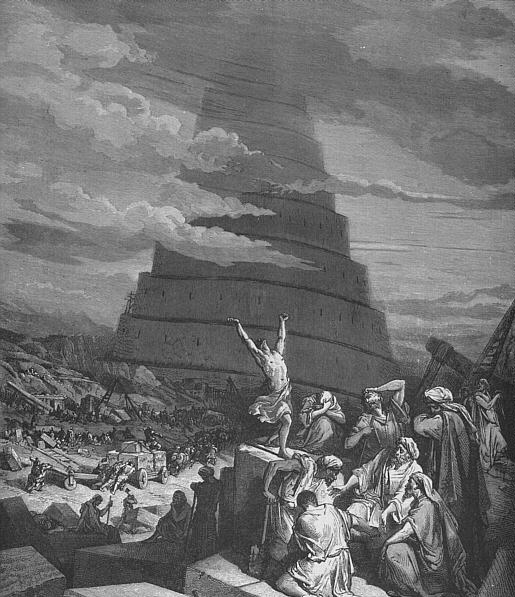

My First Tangle With the Tower of Babel

2013-04-26

A while back, I was reading the blog of somebody smart (can’t remember who), and a comment jumped out at me: “If you really want a black belt in computer science, try writing a programming language. The depth and breadth of experience you get when you invent Python or Lisp or Smalltalk or C++ or C# — and implement its ecosystem, not just code a parser for a CS class — gives you a wisdom and education that’s rare and precious.” (I’m paraphrasing here, but that’s the gist of it.)

Sounds good, I thought. I think I’ll give it a shot.

I began doing research and taking notes. I thought hard about which features I liked and detested in programming languages. I read critiques and tributes to various languages by detractors and fans. I identified pieces of syntactic sugar that I wanted to support. I took a wad of existing code and tried to rewrite it using the language I was drafting. I picked some conventions for filenames. I played with yacc and antlr and experimented with definitions of context-free grammars.

And then I stalled.

It wasn’t good enough.

My new language was nifty. It combined a lot of the best features of my favorite languages: closures, list comprehensions, lambdas, static if, robust type inference, unified function call syntax, with blocks, variadic templates, mixins, nullable primitives, built-in support for design by contract, and more. I actually believed (perhaps naively) that I knew how to implement a good portion of these ideas in a compiler.

But I began to intuit that nifty != great. And the longer and harder I thought about it, the more convinced I became.

Some of you know that I have a background in linguistics (which may explain why this project appealed to me). One of the lessons I learned in my graduate program is that language and world view are profoundly related. Choices we make in our languages affect our thinking, not just our productivity. My favorite example is the from Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, by George Lakoff: the Dyirbal language in Australia has four “gender” categories for nouns, and one of them includes everything in Lakoff’s title. You can’t talk about nouns in this language without using its gender mechanism, and this requires you to perceive and communicate categories according to its system. Mental models matter.

I connected this insight from natural human language to my experiment with computer language creation like this: All of the coolness I was throwing into my language wasn’t changing the way a programmer would think about a coding problem all that much. Sure, some of these innovations would let you short-circuit a problem, eliminate redundancy, write tighter or simpler code. But if I could port java or python into it more or less directly, then the languages were kissing cousins, and I didn’t feel like I could go out and evangelize my creation as being better enough to be worth the bother of a new learning curve. Programmers have better things to do than learn languages just for fun, and I have better things to do than to write a vanity language.

I turned to deeper investigations. I was intrigued by Alan Kay claiming that OOP was misnamed and should have highlighted messages, with objects as a secondary concern. I downloaded Smalltalk anlayed around a little.

I spent some time studying bugs. Why do they happen? Is there a way to make a language discourage or prevent them, and is the juice worth the squeeze? Can a language be immune to certain kinds of tech debt, by design?

I investigated some more exotic (largely functional) languages: Erlang, Haskell, OCaml, Clojure. I learned a little Lisp. I read an insightful essay that made me think about the social aspects of programming languages and about the personality and zen of language communities.

I have concluded that in order for a new, general-purpose programming language to provide significant value to the community, it doesn’t just have to be Turing complete and cool. It must:

- Have a consistent and powerful organizing paradigm that inspires creativity and design insight. (Lisp and Smalltalk are both outstanding in this dimension; Java's a bit anal about OOP but I think misses the forest for the trees [nod to Yegge]. PHP is awful on this dimension, IMO.)

- Solve compelling problems unusually well. (C or C++ is the go-to answer for performance; Perl used to be the de facto solution for serious text crunching, before other languages matured their regex libraries; Ruby's great for MVC web apps...)

- Attract a community of people that are disposed to cooperate and that buy into the zen of the language. (This is Lisp's fatal weakness; it attracted a community, but it was a community of maverik loner geniuses who used immense power to reinvent everything per personal preference. Java, Python, Ruby, and C++ are strong here.)

- Advance the state of the art in significant ways. (I'm not sure a language has truly changed the way we think about programming problems for a generation. See Alan Kay's Turing Award lecture. D pushes the limits of a C/C++ worldview pretty darn far, but it's a proximate evolution, not a quantum leap. Some experimental languages out of academia are promising, but are too weak on the other dimensions to get any traction. Am I wrong?)

So I’ve had my first tangle with the Tower of Babel, and I’m now in ponder mode. What would truly change programmingradigms for the better in a basic way?

I think the answer may lie in system thinking may help. I’m now studying shared transactional memory, actor systems, variants of declarative programming, and so forth. I’m not sure where I’ll end up, but I plan to blog about my discoveries as I go along. Look for posts in the “better programming language” category…

I am also very interested in your insights. What do you think would make a new programming language not just fun or interesting, but so compelling that you’d have to master it and tell all your friends?

Comments-

Julie Jones, 2013-09-08:

I think you really hit the nail on the head with "change the way we think". Of all the languages that come and gone none have really changed the way we think about solving problems in the last thirty years. There have been a few that had potential, but I can't think of any that brought a new paradigm to light. Erlang is the only one I can think of that has picked up a decent following by managing to make one previously hard thing easy (multi-processing), but it is hardly revolutionary.