Codecraft

software = science + art + people

On Forests and Trees

2015-09-02

When an English speaker is drowning in details that make the big picture hard to see, she might complain, “I can’t see the forest for the trees.”

It’s an odd expression, partly ironic and partly humorous. When I hear it, I sometimes think of my sister, who, after moving from Indiana to Utah, complained that the mountains were getting in the way of her view. (Her tongue was firmly in her cheek… :-)

The expression also describes an important problem of software engineering — one that a lot of engineers don’t understand well enough. It’s a problem with generalization.

Why generalization matters

Generalization is the process of finding emergent patterns in our creations or our processes, and taking time to codify the patterns so as many specifics as possible become unremarkable. It’s among the human mind’s most powerful techniques for complexity, and it’s a hallmark of vigorous thinkers in any technical discipline. I like what Hegel said:

An idea is always a generalization, and generalization is a property of thinking. To generalize means to think.

Many techniques in software engineering are rooted in this mode of careful pattern-oriented thinking. Interfaces, inheritance, and class instes group features and data underlying many concrete variations. Subroutines generalize the flow of logic in an algorithm. Refactoring often collapses differences that are less useful than originally guessed. Templates and generics and design patterns provide cookie-cutter outlines into which details can be plugged. Modules and components and libraries let us mix by formula. Fuzz testing tries to generalize about acceptable inputs to functions.

Where code is wisely generalized, maintenance goes down, testability goes up, and it’s easy to pernicious tech debt.

Drowning in details

With obvious benefits and technology built to help, you’d think software engineers would be wizards of generalization in what they write, test, and manage.

Unfortunately, I find this skill surprisingly rare in techies. It exists, to be sure — but it’s disheartening how often simple and high-value generalization gets neglected.

Example 1: I spent a couple months this summer refactoring a large, old, mission-critical codebase that contained both an embedded web server and an embedded web client. The code had multiple routines to parse incoming requests and responses. These were big, complex routines, poorly tested and full of unhandled corner cases — and there was no relationship between request parsing and response parsing, even though http requests and responses have identical structure after the first line. Big generalization miss!

The code also had numerous functions to help build requests and responses by accumulating pieces of data in a buffer. Most of these functions were similar in the way thmanaged header values like Content-Length and Content-Type, but they used buffers of different sizes, wrote to them in different ways, and handled and reported errors inconsistently. Useless divergence… In one case, a function was nearly 1000 lines long, and had scores of repetitive statement clusters that inited a pointer to a string constant, then looped over the chars in the constant, appending the char. Why the author never thought to use strncpy() is a mystery to me; I shrunk the function to 1/3 of its original size with that one change. (Aside: 3 of the repetitive statement clusters turned out to increment the pointer differently from the others. I had to write a test before I figured this out; that detail was totally obscured and would never have been caught by a casual maintainer. It hadn’t been commented as a weirdness, either.)

Example 2: A few months ago, I noticed that a volume on one of our production servers was nearly full. No generalized from one problem to a systemic weakness very well.

What generalization looks like

The easiest way to tell that code’s been wisely generaed is to ask yourself this question: “Can I see the forest for the trees?” If a quick glance at any level of detail (a class, a function, a module, a project definition) gives you a broad, useful picture of what’s inside — with opportunities to drill deeper as needed, but without overwhelming noise — mdash; then a careful generalizer has done their job. Same deal if lateral and hierarchical and temporal relationships are obvious. It’s not an accident that I’m describing “good code” here — the kind we all like to work in…

Generalization is partly why boilerplate comments are worse than useless, and bears on why encapsulation and loose coupling are so crucial.

Why we don't generalize

I’m not saying that generalization is easy, though.

One reason we don’t generalize is because we are being solvable — or at least improvable.

Another reason we don’t generalize is because we’re addicted to details. I have heard performance zealots say that they couldn’t break up massive C/C++ functions because they couldn’t trust the compiler to inline like it was supposed to. This is utter nonsense. Setting aside the (largely valid) argument that the compiler is usually smarter about performance optimizations than the programmer, you can always use a macro, for pete’s sake. I’ve heard similar mindsets in laments about inheritance and vtables, the inefficiency of regexes, the inconvenience of private member variables, and lots of other features in every programming language I know. In each case, the technical points on which the rationalization rests may be narrowly valid — and maybe it matters in a very specific context — but there are almost always ways to generalize better or more cleanly than we like to claim. We should hang on to as few details as we have to.

A third reason we don’t generalize is because we don’t think hard enough, or we’re not smart enough to notice a pattern. This happens to me a lot; I find that I can’t generalize in code that I haven’t invested in deeply. It’s too easy to make mistakes.

A fourth reason we don’t generalize is because our tools and languages discourage us. Java, for example, is ridiculously detail-heavy in its management of data types: to declare a variable, you usually have to declare its type and name, and then set it equal to a new</co object of exactly that same type, named all over again. Do an egrep through a java codebase sometime, looking for typename identifier = new typename. It's silly. You can have just as much type safety, without the mind-numbing repetition, as ML proved, and C++11 discovered with the introduction of the auto keyword.

There are lots of other examples. Aspect-oriented programming attempts to formalize generalizations that permeate or cross-cut a whole codebase; to the extent that AOP is awkward, we are generalizing against the grain of our tools. intent programming language I’m writing is an attempt to address this problem; perhaps I’ll blog about that soon.

Call to action

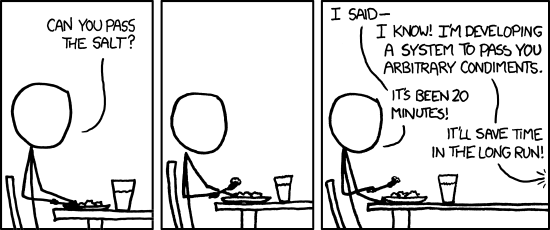

Pragmatism always matters, of course; it may not be worth our time to generalize in every case. :-)

Nonetheless, the best tech folks that I know are much better at this skill than the middle of the bell curve, and I don’t think that’s an accident. I’d like to see us, as an industry, do a better job of turning implicit patterns in our everyday engineering work into method, structure, and reusable building blocks.

Where do you have code, or processes, that are calling out for this sort of attention?

Comments-

-

-

-

-

-

-

David H, 2015-09-03:

This post really resonates with me as it reminds me of a lot of the technical problems I'm dealing with now. So how did we get into these kinds of messes? To me it doesn't seem to be a matter of not being in the top 15% of the bell curve and not being smart enough to see generalizations. Rather I see it as natural outcome of problems with any resource over which there is shared stewardship. It has been called "the tragedy of the commons." It occurs when there are problems that require more authority and more perceived responsibility than one person or one small group of people with common shared interests can solve. In the case of the embedded web server you describe, it sounds like it was organically developed by multiple people over time, code accreted here a little, there a little, by people trying to solve a particular small problem or fix a specific bug. Most changes were made by people who did not feel empowered to do cleansing refactoring. If they had attempted such a thing (and they might have wanted to) their bosses would likely have stopped them and told them to focus on the task at hand. In the case of the overflowing backup files, you could have fixed that problem yourself, if you had been given privileges. The people that had the privileges obviously didn't have the same feeling of urgency. It's not that people aren't smart enough to see the generalizations. It's that there isn't the right confluence of people who both care enough about the problem and are empowered to solve the problem. In my current job there are definitely a pile of problems of this nature to be solved. I am working out a strategy (with the knowledge and consent of my boss) to multiplex between working on current urgencies and doing the kind of cleansing and fixing that needs to be done. It sounds like you are doing something similar.

Daniel Hardman, 2015-09-03:

It's a good point, David: often our inability to generalize is caused by circumstances that we can't easily change. There can be complex, mutually reinforcing reasons why we don't spend time on long-term housekeeping. Tragedy of the commons, indeed... Perhaps what makes the most difference is not different intelligence, so much as it is an "if it is to be, it's up to me" attitude that leads us to take the bull by the horns and not allow the status quo to get the better of us.

Nathan, 2015-09-03:

The type of generalization used matters a great deal. Our brains like familiar patterns and habits, and its very easy to use the most comfortable pattern without considering alternatives. That is what makes jokes like "The Evolution of a Programmer" so funny (http://www.ariel.com.au/jokes/The_Evolution_of_a_Programmer.html). I'm also reminded of the "Zen of Python" quote, "There should be one — and preferably only one — obvious way to do it. Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch." A generalization idea needs to resonate with more than your own mental model, or it may not be accomplishing what you set out to do. Consider debates about type systems such as those found in Python and Haskell — they both accomplish very different kinds of generalization with very different outcomes. Which form of generalization we chose depends on *both* technical requirements and how we best communicate those intentions to the other humans who will be working with the code over time. For a generalization to be sustainable it must communicate your intent more clearly than the alternative. This is why its a joy to work with programmers who are both life-long learners, and effective communicators. They are more likely to understand your abstractions as you intended (even if you missed the mark when you coded it), and communicate effectively enough to teach about what is found in the code base so that the abstractions stick.

Daniel Hardman, 2015-09-03:

It seems to me that you've made a very astute observation, Nathan; just using what's familiar or easy to express in our favorite worldview is often suboptimal, but we fall into that trap all too easily. Careful thinking is advised. I know of no easy and objective way to prove that a particular mental model is the ideal choice. Tech holy wars make me think no such way exists. However, I've begun to wonder if semi-objective measures of "good" or "better" choices might be possible: the net promoter score of a codebase among the people that develop and test it, for example. I don't think mindless measurement of these metrics is a panacea, but some attention to such numbers might be helpful in raising awareness and triggering discussions. In the meantime, I think we depend on the talents of the sort of programmer you identified, that helps to bridge communication gaps and keep imperfect people and technology as productive as possible.

Andy Lawrence, 2015-09-07:

One form of generalization is finding ways to push functionality as far up the class inheritance tree as possible. If you are working with a modern code base, you probably have some fairly deep class hierarchies. Every time you need to add a new method or a private variable to a class, first think "are there other classes (parents or siblings) that could benefit from this as well". You might need to make it a little more general to make it apply to multiple classes, but it can really help you not have to reinvent the wheel next month or next year when another class needs the same thing. The project I am working on has lots of objects that are similar. When I add a new feature, I try to generalize it as much as possible, I can often add it to a base class near the root of my tree. All the child classes can then benefit from the added functionality. I know this is a basic class design and implementation practice, but how many times have we seen something like a SerializeAndSaveToDisk method that was written a dozen times because someone different added it to lots of leaf classes over time (and probably named it differently in every case so it is difficult to notice unless you are looking for it).

Daniel Hardman, 2015-09-08:

Nice example, Andy — both in general, and with the specifics of serialization. I agree that putting functionality higher in the hierarchy is often a big win. It's not mechanically difficult to push the code there, but seeing the need to do so is a challenge at times. Maybe we need to get all CS students to have a learning exercise that teaches this specific issue. In a related vein, I'm coming to believe that the biggest predictor of code health isn't how smart we are to start with, or how good our tools or design decisions are — it's how often we refactor as we get smarter and more confident about the "right" shape of the code.

Sparks Of Melody, 2024-02-26:

Thank yoou for being you