Codecraft

software = science + art + people

When good comments mean bad language

2013-08-22

I’ve had an epiphany.

For years, I’ve urged developers to write better comments. I still claim that’s a good idea (a very good one), but as I’ve pondered what a better programming language might look like, I’ve come to an important conclusion:

A lot of "best practice" commenting is just workarounds for inadequate language design.

This might seem like a crazy or arrogant claim. The Wirths and Matsumotos and Hejlsbergs and van Rossums and McCarthys of the world are incredibly smart people; how could I claim to know something that they do not? Each of these language designers has probably forgotten more about computer science than I will ever learn.

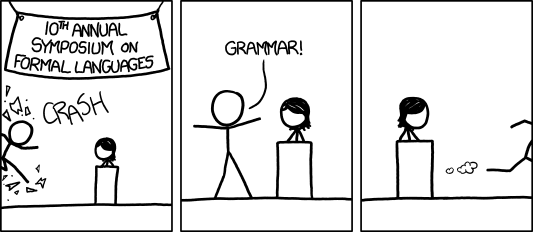

And yet, I think Randall Munroe (the cartoonist at xkcd) was right to make fun of our industry’s facile assumption that context-free grammar is all you need to know about formal language:

To show you what I mean, I’ve inlined snippets of code from a variety of programming languages below. Don’t worry about digesting them carefully right now, but give them a quick glance and then move on to my analysis, and see if you agree with my claim about an unhealthy pattern.

Exhibit 1 (C++)

/**

* Process serialized string; update attr for associated Vehicle.

*

* Assumes string starts at first attr~value pair, not at vehicleid

* (ex. format: vehicleid:=;[=;])

*

* @param serializedAttrs (I) — can't be null

* @param attrList (O) [optional, should be empty when passed in]

* @param maxLoadCount (I) [optional, range [1..100); -1=="all"]

*/</span>

int Vehicle::LoadVehicleFromStr(const char * attrs,

std::list * attrList, int maxLoadCount)

{

if (serializedAttrs == NULL || *seralizedAttrs == 0)

return FALSE;</pre>

Exhibit 2 (C)

while (*ptr != '')

{

if ((tail = strchr(ptr,';')) != NULL)

/************ about 100 lines omitted... ************/

if (tail == NULL)

break;

ptr = tail + 1;

} /* END while ((ptr[0] != '') */

Exhibit 3 (java)

/**

* Tracks where/how an app uses folders on disk.

*/

public interface DiskLayout {

/**

* Record where an app installs and stores data. This method

* is used instead of setters on individual properties because

* changing root locations typically has cascading effects on

* many other disk locations.

*

* @param installRoot

* Path to folder where package is installed. Need not exist,

* but must be a conceivable path (e.g., not null)

* @param dataRoot

* Path to folder where application stores data. Same

* constraints as with installRoot.

*/

void configure(String installRoot, String dataRoot);

/**

* The install root is the folder where an app looks for

* .bin, ./conf, ./lib, and so forth. May be read-only to this

* process.

*

* @return Fully qualified path where app is installed.

*/

String getInstallRoot(); /** @return Fully qualified path where app stores its data. */

String getDataRoot();

Exhibit 4 (python)

def start(timeout, name='Timeout Monitor', killfunc=_defkill_func):

'''

Start a thread that forces exit if we hang. Return a monitor

object that can be kept alive with .keep_alive(), released

by calling .stop().

'''

monitor = Monitor()

kill_thread = threading.Thread(target=_kill_process, name=name,

kwargs={'timeout': timeout, 'killfunc': killfunc,

'monitor': monitor})

kill_thread.start()

return monitor

Exhibit 5 (C#)

/// </span>Give cash from my wallet.</summary>

/// The amount of cash to give</param>

/// A</span>mount I gave, or 0 if I don't have enough</returns></span>

public int GiveCash(int amount) {

if (amount <= Cash && amount > 0) {

Cash -= amount;

return amount;

} else {

return 0;

}

}</pre>

Analysis

What do these snippets have in common, as far as comments are concerned?

- Most of the comments are useful. They may not be perfect, but at least they are not inane comments that just distract readers.

- A lot of the comments explain the semantics of parameters and return values.

- Most have at least one usage of a "doc comment" style (allowing comments to be transformed to developer documentation).

- Several of the comments are inaccurate in one way or another.

Taken individually, these observations are hardly earth-shattering. But if you step back from the details and squint a bit to see just the rough details, a pattern emerges: these comments (and many, many others that I've read or written over the years) are all a sort of kludge. They tell the programmer something using a back channel, because the language they supplement won't let you communicate the idea directly. And that's a shame.

Let me show you what I mean.

In Exhibit 1 (C++), the author of the code obviously cares about preconditions. He or she has gone to some trouble to differentiate between IN and OUT parameters, and to explain the contract between caller and callee. In spite of an error in describing the constraints on the attrs parameter (it isn't just NULL that's illegal...), this is likely to help a maintainer or consumer of the code quite a bit.

But it doesn't help as much as it ought to.

If a C++ function declaration required you to specify the semantics of each parameter and return type, the compiler could use knowledge about preconditions to make better optimization choices. It could enforce the semantics in a number of clever ways. Unit tests could be generated automatically. The behavior of the function and the knowledge imparted by generated developer docs could be guaranteed to stay accurate and in sync.

Too bad the scope of the C++ language ends with syntax, not semantics.

A detour into the history of linguistics

I should explain that snide comment.

When I was doing graduate studies in computational linguistics at BYU, I spent quite a bit of time studying generative grammar, transformational grammar, and related systems. These are equation-like approaches to analyzing human languages; they map a specific language instance onto formal structures that can be manipulated algorithmically, and they aim to generate an abstraction that's language-neutral and hard-wired into the human brain. These grammars became de rigueur when computer science and mathematics met linguistics back in the '60s, in the person of Noam Chomsky and his disciples. You can imagine how these grammars might resemble that holy grail of compiler designers, the context-free grammar.

Yep.

While all my CS confederates were writing their own programming language and a lexer/parser to turn it into machine code, I was performing eerily similar exercises on human language as I studied machine translation. If you can reduce a sentence to an intermediate, language-neutral representation and then re-render it using the surface-level conventions of a different language, translation should be easy, right?

Except it doesn't work that way.

Oh, sure, we have good enough translation that lets us say "Where's the bathroom?" in a hundred languages from an Android app. That's mostly just dictionary lookup with fuzzy matching and a few other bells and whistles. But when Dan Quayle accused Al Gore of "pulling a Slick Willy on me"[1] during vice presidential debates in 1992, 50 million Americans understood exactly what he meant, immediately — even though the phrase he used did not exist in any dictionary, had never been uttered to anyone in the audience, and mapped onto a linguistic structure that suggested none of what he managed to imply. (I'm not lauding Quayle here, just making a point about language.)

This sort of phenomenon in language gives computerized translation fits, because syntax and a dictionary don't explain it.

It tells us that there's more to language.

There's semantics, for example. (And numerous other layers/aspects as well. Deep topic. Go read The Possibility of Language, by Alan Melby, if this sounds intriguing.)

Analysis again

Back to the exhibits.

Exhibit 2 (C) identifies the end of a block with a comment — again, because the language doesn't give the programmer any other way to do so. The fact that there's been drift (the comment maps back to an "if" statement that's been tweaked since the comment was created) highlights why this mechanism is less than optimal.

Exhibit 3 (java) shows conscientious use of javadoc, but notice how the semantics on installRoot are spread across two separate function comments, and how the semantics for dataRoot reference knowledge about installRoot in an ambiguous way. If we "compiled" the semantics of these parameters, logical inconsistencies could be flagged, implicit relationships could be disambiguated in developer docs, and so forth.

Exhibit 4 (python) is notable for its terseness. Python functions don't have to have consistent return semantics (exit a function at point A and return None; exit at point B and return an int; exit at point C and return a dictionary or a 6-way tuple — the interpreter doesn't care). The programmer has compensated by telling the caller what to expect. Telling the interpreter what to expect, instead, would provide a standard way to inform the programmer, and facilitate tests or sanity checks that could prevented many of the python bugs I've written over the years.

Exhibit 5 (C#) is more of the same. Notice the logic error in the comment about when 0 is returned. Again, fixable and better if managed by compiler.

Could a programming language really encode more semantics? And could it do so elegantly and easily?

Absolutely! Ada addresses the issue of range precondition for parameters by changing the way programmers think about types. Instead of short and int, you have stuff like this:

type Day_type is range 1 .. 31;

type Month_type is range 1 .. 12;

What about the C example, where a programmer wanted to delimit the end of a block? Well, bash has one solution:

if [ conditional expression ]

then

statement1

statement2

fi

We simply mark the end of the block in a way that ties it back to the statement that began it. Ada and Pascal do something similar. Python elegantly obviates half of the issue by taking indents more seriously. But for gnarly nesting, I might like something like this:

while we have more items in the linked list (*ptr != ''):

if we can find another semicolon ((tail = strchr(ptr,';')) != NULL):

# about 100 lines omitted...

end if another semicolon

end while more items in the linked list

In this imaginary language, a block like while or if can have an explanatory comment between its initiating keyword and the parenthesized syntax that defines its condition. Then, when we unnest, we can optionally add an assertion about which block is ending. The assertion is invoked with end followed by whichever keyword began the block, plus a few words from the comment to identify which block it is. The compiler can then alert us if we've unnested incorrectly, and programmers can remember where they are based on the intent rather than the fiddly details of the block's syntax. With no clutter. And no Pascal-style mandatory begin or end.

Advanced semantics

How about the "can't be null, can't be empty" preconditions? How about more complicated semantics? Won't we end up cluttering the language and becoming horribly verbose? Java's annotations and C#'s attributes offer a glimmer of hope. In my explorations of a better programming language, I've been playing around with a cousin to this sort of mechanism, which I'm calling "marks" (after the linguistic concept of "markedness"). Here's a sample, just to whet your appetite:

class vehicle: +threadsafe

func react_to_hazard:

takes:

which_hazard_type: hazard_type +sensable

hazard_location: coordinates +within(50meters, this.location)

descrip: str +text(1, 25) -nullable -empty

severity_of_hazard: int +range(0, 100)

returns:

coped_safely: bool

There's a lot here, and I'll explain marks in greater detail in another post. For now, let me just say that the marks are the small words like +threadsafe that decorate parameters, classes, and so forth. They are not reserved words in the language, and the parser doesn't have to work all that hard (notice the different color for func). Marks in this chunk of code are declarative rather than algorithmic; they can be enforced in one or more places in code that the compiler generates.

Some marks are preconditions. Others express units (meters), and can be used to guarantee that you never wait 1000 seconds for a timeout, when 1000 milliseconds was what you intended. Like decorator mechanisms in other languages, they're easy to build and add. But there are some big differences, such as the fact that it would be easy (and often, automatic) to connect semantics implied by these marks to compiler behaviors of a hundred useful varieties. And the fact that implications of marks would be an aspect-oriented programming feature, where you can inject (in IoC fashion) the desired treatment by the compiler or a runtime environment.

Think about the semantic density of this snippet, and how it compares to the semantic density in any of the exhibits listed above. Would it be cumbersome to write or read code like this? I don't think so.

Now notice how many comments this snippet has.

Don't get me wrong — we need comments. I am a big advocate. I just wish we didn't have to use them as a crutch to compensate for languages that do too little to help the user and the compiler be smart.

[1] I found a youtube clip where Quayle says "pull a Bill Clinton on me", but I can't find one for "pull a Slick Willy on me". Maybe I'm remembering it wrong. Either way, the linguistic phenomenon is the same.

Comments-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

trevharmon, 2013-08-22:

Excellent article, Daniel. I wonder where the line is between accepting a certain amount of context-sensitive ambiguities as just being a part of human communication (which programming is, in some sense) and allowing the creation of arbitrary grammers like in Perl 6 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perl_6_rules#Grammars), which I would expect leads to the emergence of dialects, like we see in spoken and written human language. Don't get me wrong, I agree with the premise and conclusions of the post. I just wonder how far we can really go in marrying context, semantics and syntax without making it overly burdensome to manage and grok. Putting forth a logically flawed argument, I really don't want to have to learn a new grammar for every function call. :-) Like always, your article provides me with much to ponder and consider.

Samuel A. Falvo II, 2013-08-22:

Extreme programming advocates coding without comments to the greatest degree possible, but no more than that. The idea is to use well-chosen, verbose names for types and methods that work on those types. For example, instead of your C++ code in listing 1, we might see: [1] int Vehicle::VehicleFromString(const char * source, std::list * attributes, int maxLoadCount) { [2] if(ISNT_EMPTY(source)) return FALSE; [3] if(!(LIST_EMPTY(attributes)) return FALSE; [4] if(!BETWEEN(maxLoadCount, 1, 100) && (maxLoadCount != -1)) return FALSE; In line [1], some names were changed to protect the intent. In general, programming communities seem to have adopted the XfromY naming convention for procedures used to convert from one type to another. It seems that's what this method is doing, so I made the appropriate change. Following conventions reduces mental burden. Additionally, I changed the string parameter's name to "source", since that's the source code of the data. Presumably, VehicleFromString is a parser, and you feed source code to parsers. Also, notice the code you wrote in listing 1 is buggy — you have no parameter named serializedAttrs. ;-) Your list of attributes implies a plurality of attributes, and so I just called those "attributes." Short, simpler, and carries the full semantic load of the concept. In line [2], [3], and [4], I use preprocessor macros to make common range-based and pointer validation checks succinct and easily re-used. Indeed, if the "return false on invalid input" thing is a pattern, then each if-statement can be replaced by a suitable macro, or even the entire block of if-statements if they repeat often. Now, people can derive everything you just expressed in comments by reading actionable source-code, and it's English-enough to be understood by a large number of people; the only prerequisite is that they know how to read and understand C++. As far as _why_ this code was written the way it was, XP advocates looking at your commit logs in your revision control system of choice. E.g., one could use "git blame" to identify who last affected the code you're interested in, and it will also show the most recent commit hash for each line in the code. Use "git log" on that commit hash to then read why the change was put in place. The advantage to this is that a _single comment_ can then apply automatically to a large number of related changes in a plurality of source files. Normal program comments _cannot_ do that, no matter how hard you try. One last thing about coding preconditions like this, if I may. This is such a good idea, in fact, that Eiffel, Sather, and if I recall correctly, Ada actually has first-class support for pre-conditions, post-conditions, and class-wide invariants, expressed using real, actionable, compilable code. They can be turned off with a compiler switch if performance is too adversely affected. This kind of ruthless refactoring can apply to virtually any language. Your listing 2 can be easily rewritten: while (*ptr != '') { if ((tail = strchr(ptr,';')) != NULL) process_line(ptr, tail); if (tail == NULL) break; ptr = tail + 1; } Full stop. That's all you need. If you need more than three variables shared, use a common data structure and pass in its address, like so: struct Blort b; // ... while (*b.ptr) { if(!(b.tail = strchr(b.ptr, ';'))) break; process_line(&b); b.ptr = b.tail + 1; } Linguistic idioms come into play as well; *ptr != '' looks weird to me, so I rewrote it simply *ptr, as is common in most other C code. Also, restructuring if-statements to serve as invariant guards, instead of expressing high-level thought processes, often simplifies the code. Compare the original C code to that above. It's requires fewer characters to type in, proportionately reducing the opportunity for inadvertent bugs. Of course, it's perhaps best to wrap the entire while-statement in a function of its own as well. Be sure to use a good quality name for it! I should point out that Forth is the king of writing expressive code, *IF* you know how to use its power for good. The secret is to write your code declaratively: ( etc... ) : semicolon ptr @ [char] ; strchr dup if process-line then ; : line semicolon dup 0= if r> 2drop then ; : lines begin ptr @ c@ while line 1+ ptr ! repeat ; To the uninitiated, this is baud-barf from the 80s. But, let me explain... The 'lines' definition expresses the same outer while-loop that the C code does. But notice I expect the response for 'line' to be a non-null value which I update ptr with. This implies, by reading this one line, that 'line' _must_ check for this condition and act upon it accordingly. I simply don't have to worry about it at this level of abstraction. 'line', attempts to process a semicolon-delimited line. Somehow. Again, details aren't important at this stage. But, we expect it to return a value (the tail pointer). If zero (null), we the return address of line off their respective stacks, and return. Popping the return address of line will terminate the activation of 'lines', which is why we need to clean up the stack here, and not within lines itself. Still, we've expressed in just two lines of code what it took 4 in C, and it's every bit as readable, once you know enough Forth to competently read it. Also notice that code reads left to right, like English; it does not read top-down, and also notice that you can read individual lines of code in total isolation from any other line, and derive useful knowledge from it. That's powerful. Note that Forth prefers short names over long names, but this is due to Forth's context sensitivity. A program that reads lines of text from a file and uses them to draw lines on the screen will likely have two or three definitions of 'lines', if not of 'line.' This is also incredibly useful, and I often wish other languages provided similar behavior. But, I digress. Notice also that I can refactor common predicates into definitions that manipulate return and data stacks, and as long as I call these definitions from words that have the same stack shapes on entry, I can re-use these predicates WITHOUT having to rely on macros, as I would in C and C++. This not only improves the readability of code, making it that much more declarative in nature, but it also saves valuable program space by preventing repetitious code in the compiled binary image.

tianyuzhu, 2013-08-22:

With some effort, we can convey a sense of semantics in C++. For example we should be able to write: int Vehicle::LoadVehicleFromStr(std::string serializedAttrs, optional attrList, IntRange maxLoadCount);

Now optional isn't in the standard yet, and IntRange probably won't ever be in the standard, but you can write both types fairly easily.

In fact, efficiently encapsulating semantics in types is something that C++ specializes in. And of course, since C++ is statically typed, doing so allows the compiler to verify semantics for you.

Here's a short list of how different types have different semantics when used as function arguments. For some type T:

T: means you're passing object by value. The function gets it's own instance of T and owns it (will destroy it or transfer ownership of it to somewhere else).

T &: A reference to an instance of T. It can't be null. The function does not own it.

T *: A pointer to an instance of T. It can be null. The function does not own it.

optional: Like passing T by value, except it can be "null".

unique_ptr: Like "T *", except the function gets unique ownership of the instance.

shared_ptr: Like "T *", except the funciton gets shared ownership of the instance.

Daniel Hardman, 2013-08-22:

Yes, I agree that making language more rich can be taken too far. Python is one of my favorite languages, but it foregoes a lot of the ideas I'm advocating, in favor of terseness and simplicity. And it works. I think the reason why has something to do with the problem domain that's its sweet spot, which I think is on somewhat smaller and less complex projects than the sort I've spent most of my career leading. When you need to rip through a thousand files and slice and dice the data they contain, for a quick-and-dirty project, you don't really want "semantic density" getting in the way. You can hold the whole problem in your head, more or less, and you just want to get on with expressing the solution. On the other hand, if you're writing a hairy system with a dozen or a hundred other programmers at multiple sites, and it will be maintained and enhanced for years to come, being crystal clear about your intentions is probably worthwhile.

Daniel Hardman, 2013-08-22:

Samuel: Your craftsmanship is showing. :-) I picked these samples from actual production codebases that were conveniently laying around. They weren't intended to be great code, only realistic. The C++ snippet is one I had to rewrite slightly to protect the (semi)innocent, and my rewrite introduced the bug you caught. In practice, I would likely do much of the same refactoring that you advocate, although I don't think I'd be as good at it as you are. It puzzles me how often my fellow programmers leave yuckiness around when they could be clearer and more terse if they spent a *very* few minutes improving the code. Maybe they look at my code and wonder why I put up with stuff that seems arcane to them. I dunno. Your comments about Forth are very intriguing. More for me to study! :-) Thanks for the thoughtful response.

Daniel Hardman, 2013-08-22:

Good observation, Tianyuzhu. Thanks for the comment. I agree that it is *possible* to express most or all of the ideas in this post, using cutting-edge C++. We must think alike. On several C++ codebases, I've done stuff like this — only to see a majority of the other programmers on the teams react with puzzlement and eye-rolling. This frustrates me. I think the reason I don't see this idea catching on in C++ is because: A) Most C++ today is still written against the C++ 98 standard (partly due to mental inertia and partly due to compatibility concerns). Sigh... B) C++ makes tons of stuff *possible* but does a poor job of encouraging it or making it attractive and easy. Look at how hard Alexandrescu had to work to write Loki for traits-based programming, and how foreign his idiom is to most C++ coders. I guess I can't blame C++ compilers for cheerfully consuming code that uses none of the techniques you've identified. The set of use cases that C++ aims to address is incredibly broad, and careful communication is not always worthwhile if you're writing small or short-lived projects.

j2kun, 2013-08-22:

Great post! My two cents: It seems to me that there's a fine line between semantics of a programming language and "semantics" as you describe it in this post. I would consider many tasks like generating unit tests and documentation generation to be programmer tools, not strictly part of the language itself. Are you arguing that these *should* be part of the language? If so, I would say you're expecting too much of semantics and the compiler. Besides, those programmers who care that much about fine optimizations are hugging the machine architecture so tightly that (I imagine) they'd rather do it themselves and have it be explicit in the code than rely on the contextual knowledge of which compiler optimization is in play at what time. I imagine the compiler would be able to optimize something if you have +range(0,N) but not +range(0,N+1) for some sufficiently large value of N, and this would just add to the contextual knowledge needed. That being said, I think you're thinking too small! With the current state of technology, why restrict yourself to text? Moreover, if you want simplicity and cleanliness without sacrificing "semantic density," why not design a language as you wish, and design an editor that transforms terse and detailed representations back and forth at the will of the coder? (say, by mouseover, or C-x M-c M-expand, or whatever mechanism you like) Or why not have the compiler learn the appropriate constraints? A dynamically written Python-style program could be transformed into a statically-typed version which can then be compiled and optimized as desired.

Daniel Hardman, 2013-08-22:

Jeremy: Thanks for a thought-provoking idea. Implementing an optimized editor along with a language is what the designers of Smalltalk did, and lo and behold, the modern IDE was born. It sounds like a lot of work, but maybe a lot of coolness would result. I'll have to chew on that for a while...

j2kun, 2013-08-22:

Have you heard of LightTable? They are already doing some things in the realm of automated test generation, but their goal is somewhat different: they wish to alleviate and add inspiration to the process of writing new code.

Daniel Hardman, 2013-08-22:

Wow! I went and watched the kickstarter video, and I started salivating. That is an awesome concept. I want to get me one, today! I'm going to download the preview and see if they do more than lisp... Thanks for the suggestion.

j2kun, 2013-08-22:

Well now that I've got your attention :) the Light Table project was inspired by a talk of Bret Victor called Inventing on Principle, and he has a second talk called The Future of Programming which I think you'll enjoy. Both bring up some very important questions about the way we interact with computers in designing programs.

tianyuzhu, 2013-08-22:

It's kind of funny because there are libraries like Guava that implement things like Optional for Java, and Java developers happily use it. Here's the thing: A) A lot of useful features like optional can be implemented in C++98. There's no excuse for not using them, especially if they're already available in libraries such as Loki. B) Although it isn't easy to implement things like optional, it's still valuable because such components are highly reusable. And honestly, they're not that hard to use.