Codecraft

software = science + art + people

Why Exceptions Aren't Enough

2012-10-09

(This post is a logical sequel to my earlier musings about having a coherent strategy to handle problems.)

Back in the dark ages, programmers wrote functions that returned numeric errors:

if (prepare() == SUCCESS) {

doIt();

}

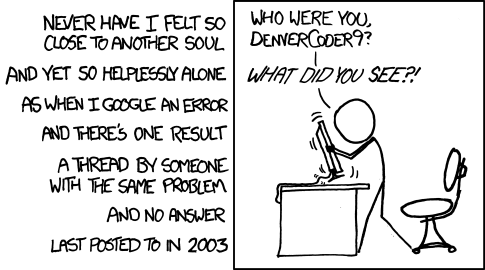

This methodology has the virtue of being simple and fast. We could switch based on the error code. A “feature” of our apps was that our users could google an error code to see if they had company:

However, as we wrote code, we sometimes forgot to check errors, or tell users about them:

prepare(); doIt();

Admit it; you’ve written code like this. So have I. The mechanism lets a caller be irresponsible and ignore the signal the called function sends. Not good. Even if you are being responsible, the set of possible return values is nearly unbounded, and you get subtle downstream bugs if a called function adds a new return value when a caller is switching return values.

Another problem with this approach to errors is that it doesn’t allow you to pass context. If prepare() is doing work in 3 phases, and it fails, it can’t tell you which phase it failed on.

If you were a C programmer and picked up C++ (or worked in a codebase built by people with this sort of background), things only got worse with the introduction of bool and enums as distinct types. It was natural to write functions that returned true on success:

if (prepareEx()) {

doIt();

}

The problem with this is that numeric-error functions return 0 (=>FALSE) for success, while boolean-success functions return true. Add 5 functions with numeric-error semantics, two that return enums, and 5 with boolean-success semantics; stir vigorously. Recipe for a large batch of bugs and plenty of headaches.

Most modern programming languages have first-class support for exceptions, which addresses many of the drawbacks of simple numeric schemes. Rich context, including nested context, can be passed. Messages can have args (good except that they complicate l10n). Lazy callers get what they deserve; sooner or later someone will be forced to acknowledge the error or else the program will abend.

Since exceptions became popular, I haven’t heard a lot of clamor from the programming community about the inadequacy of the solution.

Which surprises me, because exceptions are not the end-all, be-all answer to this issue:

- Exceptions don't offer a solution for warnings.

- Exceptions allow nesting, but not compositing.

- Exceptions allow easy categorization by class/inheritance, but not by severity, consequence, or layer of origin.

- Exceptions introduce gnarly complications across library boundaries.

- Exceptions encourage sloppiness about context.

Let me take each of these in turn.

Warnings

For the purpose of this discussion, I’ll claim that warnings describe events during function execution that a called function cannot classify with confidence into unqualified success or failure. If I’m recursively copying all files in a directory tree, and I encounter a file that cannot be opened because I lack privileges or it is currently opened exclusively, only my caller knows how to judge the problem. Some callers might consider this an error; others might view it as harmless noise.

You could easily resolve this ambiguity by fiat: make the function always treat these issues as errors, or always ignore them, and be done with it. But either choice makes your function less useful to a certain type of caller.

You could add a callback parameter to your function signature, and use the callback to assess the severity of the anomaly. This is sometimes the best solution, but it becomes problematic if the parameters and semantics to your callback vary dramatically. You also incur the overhead of invoking the callback for all possible anomalies, even if only a small subset of them are in fact interesting to the caller. This is particularly problematic if you’re making remoted calls.

Exceptions force you into either-or thinking; either something is exceptional, or it is not. They insist on unwinding the stack as soon as they are thrown. This leaves you with a binary choice. If an event of unknown severity causes you to exit prematurely, but the caller thinks it’s harmless, you’ve done less work than your contract; if you wait till the end of the function and then return the worst severity you encountered, the caller may wish you had returned earlier.

No compositing

Exceptions can refer to their cause, and can give stack traces. But what if I find 3 files, out of a directory of 500, that are not copyable? The first time, I can make an exception about the problem file. Does a second exception (and its stack trace) replace the first, or take the first as its parent/cause? Neither answer is satisfying. What we really want is a “multiple problems occurred” state that contains an array of problems. I don’t know of that feature in standard exception mechanisms.

Categorization

If I have a sane inheritance hierarchy for my exceptions, I may get some nice benefits from:

} catch(NetworkError) { ...

} catch (everything else) { ...

}

But sometimes, I’d like stuff more like this:

} catch (errors from my package) {

} catch (errors from library X) { ...

} catch (errors from library Y) { ...

}

Or:

if (myException.isRecoverable()) {

tryAgain();

} else {

giveUpForever();

}

Although you can certainly achieve these things by building on top of exceptions, I think it’s harder than it should be. I think this is one reason why so much error handling code in callers is sloppy catch-all stuff.

Complications across boundaries

I think exceptions are not a good strategy for low-level, widely used library routines, because they make too many assumptions about context. In one codebase I worked in, string-handling routines that ran out of buffer space threw exceptions. This is bad. These were functions that had to run fast, were called all over the place in tight loops, were used in singletons before or after main(), etc. Coders wanted to hook the top-level exception handler to guarantee that all thrown exceptions were logged — but even before they did this, they’d opened the app’s log file, which means they’d parsed file paths, which means they’d used the string handling functions that threw exceptions.

Throwing exceptions across remoted boundaries, or even across shared library boundaries, is not always easy, reliable, or wise, either.

Sloppy context

This is my biggest beef with existing exception models — they give programmers a false sense of communication which encourages bad habits and leads to frustrated users.

WATURI Listen, Joe. What's this Deedee tells me about an error with the catalogs?

JOE I've only got twelve. I told you.

WATURI When?

JOE Three weeks ago. Then two weeks ago. Didn't you read my stack trace?

WATURI Did you tell me last week?

JOE No. I thought you knew.

WATURI Not good enough, Joe! Not nearly good enough! I put you in charge of the entire advertising library...

(Apologies to "Joe vs. the Volcano")

Stack traces are not meaningful to end users, even if they’re smarter than Mr. Waturi. They only speak to someone with a mental model of program internals. Yet in most exception-oriented programs, whether quick-and-dirty or complex-and-sophisticated, exceptions (and often, their stack traces) end up getting logged or displayed to a user, because that’s the sum total of the error-handling strategy.

To understand how insidious this is, let’s go back to my example about copying a directory tree. Suppose I encounter the can’t-copy-because-file-is-opened-exclusively situation, and my (vastly simplified) call stack looks like this:

backupMachine() ->

handleSpecialFolders() ->

copyTree()

Further suppose that the thrown exception says “Can’t copy x.dat; file is opened exclusively.”

When a user sees this message in a log or a status bar or progress dialog or message box (either with or without supporting callstack context), she or he will have two questions:

- What are the consequences of this problem?

- What could/should I do about it?

And she will not have enough information to address either question. Why? Because copyTree() can’t know the consequences of its failure, and handleSpecialFolders() allowed an exception to propagate without providing any clues.

Best practice would be for handleSpecialFolders() to create its own exception that says, “Can’t backup the registry because a key file is locked. Image will be unbootable.” This exception would then point to the exception from the lower-level function as its cause. You’d have an accurate description of consequences for every level in the call stack.

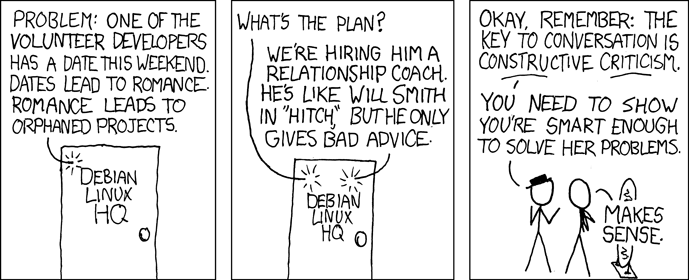

Nobody does this. It’s just too easy to let the exception propagate.

Even if they did, notice that it still wouldn’t answer the user’s second question very well. So much for good advice.

So what’s the answer?

Don’t get me wrong.

Numeric/bool/enum errors are useful when you’re writing low-level functions and you can’t assume calling layers want exceptions.

Exceptions add a rich set of possibilities.

But before we really achieve error-handling nirvana, we need something more:

You should have to go out of your way to propagate an exception without adding your own spin on its context. Instead of allowing a block of code that makes no explicit claim about handling exceptions, you should have to make an explicit claim that you don’t handle exceptions; language features should make it easy to wrap context. Dispense with an empty throw or raise. Dispense with Java’s passthrough “throws” on a function decl. Imagine something like this instead:

def copyTree(src, dest):

try:

for f in src.listFiles():

copyFile(src + f, dest + f)

except Exception e:

// Imagine that propagate requires a cause and a new exception,

// and that compiler would never allow an old exception to be

// rethrown, only propagated...

propagate(new IncompleteFolderException(msg), e)

Exceptions should declare their semantics (possibly with tags or annotations) and should be catchable by those semantics. They should also be catchable by origin.

Exceptions should allow compositing. If you do old += new, you should get composite with 2 children, and a severity that’s the maximum of all the others.

Have I covered all the biggies, or are there other features that you think exceptions ought to have?

Action Item

If you use exceptions, take a few moments to study places where you are propagating through multiple layers of code without providing new context. How could you correct this?

Comments-

-

-

-

-

-

Jason Ivey, 2012-10-10:

Daniel, We have talked about this subject at length in the past and I think you did a really great job on this post introducing the issues, deficiencies and a few of the minor enhancements you have discovered within the last few years. From a readability stand-point traditional error codes were a nightmare compared to the centralized model of exception handling. In the C world the error handling was mixed liberally throughout the entire code. Whereas in C++ and using exceptions correctly you will usually find a few central spots where the error handling occurs. Daniel's suggestion of adding context to the rich exception would change this clean C++ exception land and we will start to find more and more try-catch blocks littering the code. The error handling will once again begin to encroach upon the business logic of the application making a readability nightmare. Don't get me wrong, I think its a great idea to add context to the exception. I just hope we can either find a more elegant way to solve the problem or ask for language help (via the standard).

Daniel, 2012-10-10:

Good point about try...catch littering the code. Making error handling richer trades away some straightforwardness in the core logic. My only thought is to use "convention over configuration" to perhaps limit what you have to write. But that approach has limits; the consequences of a failure aren't something you can probably assign with smart defaults. Jason, maybe we should brainstorm an improvement to the language...

Andy Lawrence, 2012-10-10:

It would be nice if languages like C++ offered a way for a function to "drop breadcrumbs" in a manner that looks a lot like code comments, are largely ignored during normal execution, and are automatically gathered up and added to the exception context during the "stack unwind" when an exception is thrown. Pseudocode Example: void BackupEverything( ) { :) "Backing up all the data on all drives" // Drop breadcrumb for( drive = 0; drive < numDrives; drive++) { :) "Processing Drive %d", drive // Another breadcrumb for( folder = 0; folder < numFolders; folder++ ) { :) "Processing Folder %d", folder // Yet another breadcrumb ProcessFile( file ); // Call function that can throw exception } } } The statements that start with :) are breadcrumb markers that are ignored during normal execution (other than having a way to track which breadcrumbs were encountered in the code path). If ProcessFile() throws an exception, during the stack unwind operation, any breadcrumbs passed are processed (in this case by putting the current values of the drive and folder variables into their respective breadcrumb messages) and added to the context of the thrown exception. The stack unwind operation will continue up the stack and add any breadcrumbs dropped by the caller of BackupEverything(), and its caller, etc., until it encounters a catch() statement. To me, this approach would be much cleaner than littering your code with try..catch statements and remembering which messages have to be added to the exception in each catch block. Later, you can add a breadcrumb anywhere in the code and only those code paths that actually crossed it (and all all code paths that crossed it) would automatically add it to any exceptions they may encounter.

Daniel, 2012-10-10:

I love it, Andy. This addresses the need for context without some of the drawbacks of try...catch everywhere. How do we get ideas like this into the sights of language designers and standards committees?

Jesse Harris, 2012-10-10:

Another variant of poor error trapping is what I'll call "The Hanging If". A function would check to see if a POST value was non-null. If it was, it would take that passed value and assign it to a variable. And that's it. It never defined what to do if the value was unset. (Let's not even get into the complete and total lack of validation.) I found myself wonder why a developer would go to the trouble of checking if the value was null if they didn't intend to define what to do if it was. And yes, this was a case where the function was receiving a null value and causing a lovely Java explosion all over the page since the rest of the program had no idea what to do if that variable was unset.

Andy Lawrence, 2012-10-10:

I thought you were on two or three of those committees. :)